A Case of Cochlear Implantation Targeting Preserved Cerebral Cortex in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

Article information

Abstract

Temporal bone fracture and blunt head trauma was once considered as contraindication for the surgery. Increasing numbers of successful cochlear implantation are being reported. However, the outcome of cochlear implantation in severe damaged brain is unclear. A multichannel cochlear implant was successfully implanted in a 33-year-old man who had both sensorineural deafness, left hemiplegia due to bilateral transverse temporal bone fractures and severe right brain damage after a traffic accident.

Introduction

Modern technical advancements and excellent outcomes of cochlear implantation (CI) have led to expansion of the candidates in deaf patients. Accordingly, CI has become a treatment of choice for individuals, not only those with congenital deafness, but also those with acquired hearing loss like unrecovered sudden sensorineural hearing loss, presbycusis, trauma and infection. However, the effect of CI in severe traumatic brain injury is unclear and is often considered a contraindication for CI. Transverse temporal bone fractures, which typically result from trauma directed to the occiput, make up to 20% of all temporal bone fractures.1) Bilateral transverse temporal bone fractures are rare. However, it has been reported to cause severe auditory and vestibular dysfunction.2) Here we report a satisfactory experience of multichannel CI in the bilateral transverse temporal bone fractures with severe brain damage.

Case Report

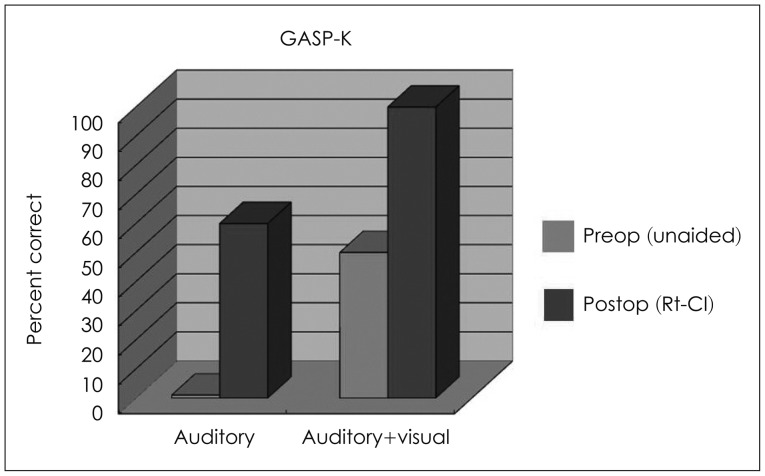

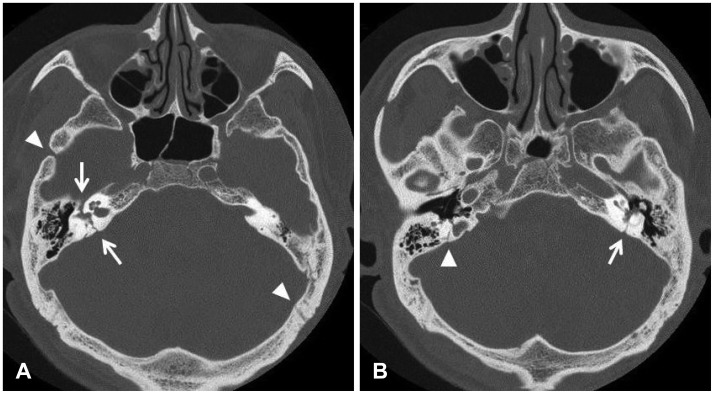

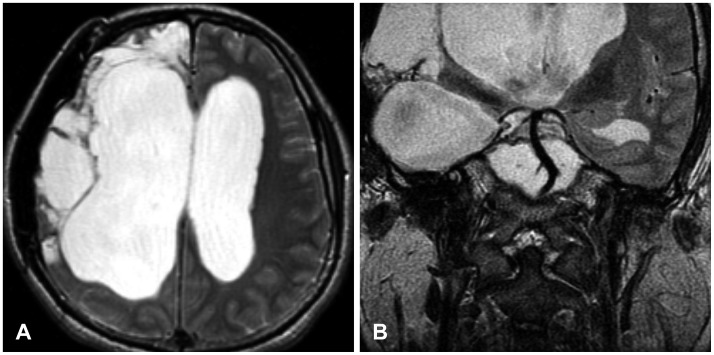

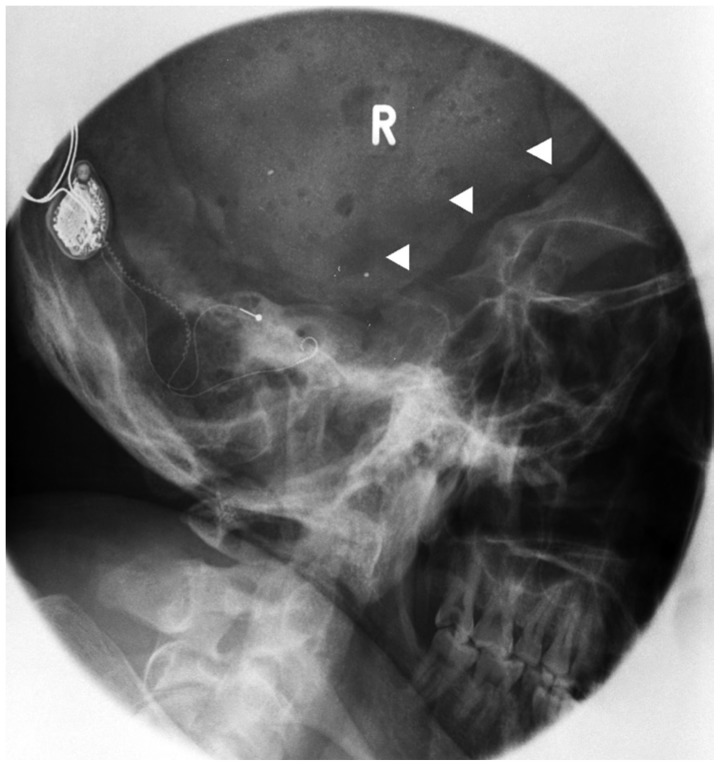

A 33-year-old man presented to our clinic with bilateral deafness and left hemiplegia. He did not have any accompanying dizziness, tinnitus, facial weakness or other psychiatric problems. He had received brain surgery 6 years earlier, due to skull fracture and cerebral hemorrhage from a traffic accident. Left side deafness and left hemiplegia occurred immediately after the accident. Four years later, he developed a sudden deafness on his right ear. Prompt steroid combination therapy was given. His hearing did not recover during a 2-years follow up. Physical examination revealed that both external auditory canal and tympanic membranes were intact. Pure tone audiometry showed a bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss. Auditory brainstem evoked response was bilaterally absent, however, there were responses to the promontory stimulation in both sides. Temporal bone computed tomography scan revealed bilateral transverse temporal bone fractures involving otic capsules (Fig. 1). Temporal magnetic resonance imaging scan showed an extensive cystic encephalomalacia in the right frontotemporal lobe and bilateral hydrocephalus (Fig. 2). However, his left cerebral cortex was somewhat preserved. Also, both cochlea showed high signal intensity on a T2-weighted image. CI was planned and conducted on the right ear. During the surgery, a fibrous band and fractured bony fragment was observed on the tympanic cavity reflecting previous temporal bone fracture. After the cochleostomy, there was no noticeable endolymph leakage and the Nucleus CI 24M electrode was inserted without resistance. Perioperative neural response telemetry test was successful and the postoperative temporal bone study showed well-positioned electrodes (Fig. 3). He had no other surgical complications. Two months after implantation, he ac-hieved a CI aided hearing threshold of approximately 40 dB, and a good Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure-Korean (GASP-K) performance score (Fig. 4). Seven years after the CI, the patient continues to successfully use the device with GASP-K 100% and a Categories of Auditory Performance score of 7.

Two slices of preoperative temporal bone CT axial scan. A: Several fracture lines are shown by arrowheads. Involvement of right otic capsule is noted (arrows). B: Facture line violating left otic capsule is also seen (arrow).

Preoperative axial (A) and coronal (B) temporal T2 weighted magnetic resonance images demonstrating extensive cystic encephalomalacia in the right cerebral hemisphere with bilateral hydrocephalus. However, left cerebral cortex and right cochlea shows preserved normal anatomy.

Postoperative temporal bone study series showing well-positioned electrodes (arrowheads showed previous cranioplasty site on the right skull).

Discussion

Severe traumatic brain injury may be life-threatening. Even if patients recover from the acute event, they may have severe sequelae that include hemi/quadriplegia, cranial nerve palsies, or cognitive or psychiatric disorder. Thus, profound hearing loss caused by brain damage was considered as a contraindication for CI. However, here we present a case of severe brain injury that, with careful evaluation and selection, successfully gained auditory rehabilitation. First, the damage site of the brain and the neural connection to the cochlea should be considered. All of the eighth nerve afferent fibers stop at the level of the cochlear nucleus and most fibers cross the brainstem to the contralateral superior olivary complex.3) A much smaller number of fibers run to the ipsilateral superior olivary complex. As in our case, there was severe right frontotemporal lobe damage after a traffic accident. At that time, the patient suffered left deafness and left hemiplegia. The temporal bone fractures, involving the otic capsule, might have been the cause of his left deafness. However, the damage of the right auditory cortex might have also contributed. When considering the site of the cochlear implant, the right side was chosen because the contralateral brain cortex was spared.

The remaining ganglion cell ought to be considered also. Profound hearing loss after traumatic temporal bone fracture frequently leads to severe decrement of surviving ganglion cells.4) Accordingly, early hearing intervention is recommended before such an event. However, a post-mortem study indicated that performance after CI does not strictly relate to the remaining ganglion cells.5) In our case, CI was performed 6 years after the traumatic event and 2 years after right sudden sensorineural hearing loss. The promontory stimulation test can be helpful to evaluate the 8th nerve function, like in this patient, who showed a response on both sides.

Labyrinthitis ossificans as a result of temporal bone fractures, and secondary infections might inhibit or prevent the successful insertion of the implant electrodes.6) The most frequent site of ossification is the basal turn of the cochlea and the successful insertion of electrodes can be achieved by drilling out the obliterated portion of the basal turn.7) As in our case, there was no severe ossification of the cochlea, and electrodes could be inserted easily. However, it is important to perform a preoperative temporal bone computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging to rule out labyrinthitis ossificans or other structural abnormalities. Several reports have suggested that if early cochlear implant is performed after temporal bone fractures, there is less time for cochlear osteoneogenesis. Consequently, there is a greater likelihood for successful electrode insertion.8)

There are post-operative considerations in temporal bone fractures. Facial nerve stimulation can become an issue. It is assumed that current leaks from the electrode through the low resistance of the fracture line can stimulate the facial nerve in the region of the geniculate ganglion or in the horizontal portion. This can be overcome by programming out the channels responsible.5) However, there was no such event in our case.

The present case shows that a cochlear implant can be a good auditory management in patients who suffer bilateral transverse temporal bone fractures, profound deafness and severe brain damage. However, the appropriate preoperative evaluations are required.