Introduction

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a common peripheral cause of vertigo at outpatient Otolaryngology clinic clinics. Otoconia inside the semicircular canals make the ampullary hair cells sensitive to gravitational forces in patients with BPPV when they turn their head to either side or when they bend their head forward or backward [

1]. Posterior canal BPPV is the most common form which is presented with up beating clockwise or counterclockwise torsional nystagmus during Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Lateral canal BPPV is determined during supine head-roll maneuver according to the direction and the severity of nystagmus which is more severe on the affected side in patients with geotropic nystagmus and more severe on the unaffected side in patients with apogeotropic nystagmus. However, presence of latency, fatigability and limited duration of the nystagmus are the main points of peripheral type of positional nystagmus. Clearance of the semicircular canal with liberatory or re-positioning maneuvers provides complete relief of symptoms.

Direction-changing nystagmus without changing the head position can be observed in patients with central pathology [

2,

3]. There is no sense of spinning during positional tests in these patients and they do not have any quick relief of balance problem. However, spontaneous changing of direction of the original positional nystagmus is also an interesting variety of BPPV [

4,

5]. A secondary reverse nystagmus in the opposite direction is seen following expiration of the original positional nystagmus after bringing the head to the provoking position. There is no agreement on pathological mechanism and this issue is the subject of discussion. The objective of this study is to review the reports about the characteristics of reversing positional nystagmus and the possible mechanisms. The data of our series with seven patients were also presented.

Discussion

Bàràny was one of the first to report the patients with positional nystagmus characterized by limited duration and fatigability [

13]. Interestingly, he claimed an otoconial dysfunction. BPPV is well known since Dix and Hallpike’s work in 1952 [

13]. It may sometimes appear in atypical forms which do not fit to the classical description. Spontaneous direction changing positioning nystagmus during head-roll maneuver was first reported in 1965 by Stahle and Terins [

5]. However, they did not present any underlying pathological mechanism. Pagnini, et al. [

6] reported six cases with geotropic type lateral canal BPPV in a series of 15 cases in which they all had spontaneous reversal of nystagmus on the pathological side. They hypothesized that primary ampullopetal endolymphatic flow is followed by ampullofugal flow due to movement of clots in the opposite direction leading to second-phase ageotropic nystagmus [

6]. Therefore, endolymphatic reflux and double-phase endolymphatic flow theory was first outlined by Pagnini, et al. [

6] in 1989.

In the following reports, Baloh, et al. [

7] in 1993 and Nuti, et al. [

8] in 1996 have emphasized the adaptation process to interpret the mechanism for the first time. Probably the reason for a new proposal was the observation of new bilateral cases since it was difficult to explain these cases with a “endolymphatic re-flow theory” due to canalolithiasis. De la Meilleure, et al. [

4] have reported 36 cases of geotropic type lateral canal BPPV with reversal of the positional nystagmus in which all of them were on the pathological side. However, proposed pathological mechanisms were both adaptation and reversal of direction of endolymphatic flow [

4]. Lee, et al. [

9] have reported 16 ipsilateral and five bilateral cases. They have proposed short-term sensory adaptation of the vestibuloocular reflex and the possibility of simultaneous co-existence of cupulolithiasis and canalolithiasis for the first time [

9]. One of the largest series was presented by Jeong, et al. [

10] They have reported 19 bilateral and 27 unilateral cases. Four patients had posterior canal BPPV [

10].

Bilateral occurrence of reversing nystagmus during head roll maneuver in patients with lateral canal BPPV is the difficult one to explain. Adaptation mechanism may not be enough to clarify the reversal of nystagmus during head turning to the healthy side since increase of perilymphatic potassium concentration would not occur with inhibition of ampullary nerve by the head turning to the healthy side. Besides, it has been reported in bilateral cases that reversed nystagmus seen during head turning to healthy side is usually less intense [

8,

9]. Ogawa, et al. [

11] reported seven cases (five bilateral and two ipsilateral) with reversal of nystagmus and proposed the possibility of coexistence of canalolithiasis and cupulolithiasis to explain the pathological mechanism for bilateral and unilateral cases. They have indicated that the debris circulating in the long arm of pathological horizontal canal and at the same time, debris entering the non-ampullary side and sinking to the cupula will cause bilateral or unilateral occurrence of reversing nystagmus. The assumption of the possibility of presence of otoconial debris at more than one different location in the same ear clarifies bilateral cases.

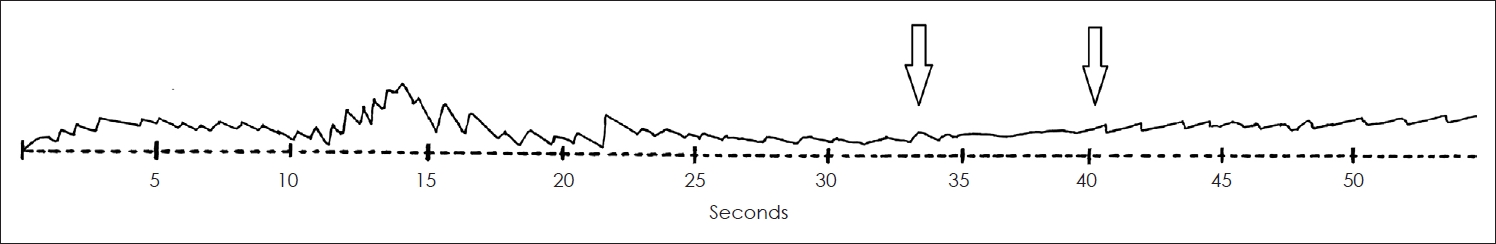

“Second-phase of nystagmus” is an interesting and an important phenomenon. First-phase nystagmus while bringing the head to provocative position is due to gravitational force which is instantaneous, fast, and strong. This leads an excitatory ampullopedal endolymphatic movement toward cupula. Second-phase nystagmus is longer and less severe. This is probably because of impulsive effect of moving debris in the opposite direction due to flow of endolymphatic reflux which results in ampullofugal apogeotropic inhibitory nystagmus. From clinical point of view, second-phase nystagmus is a supporting sign of two important issues. First, it is surely a case of canalolithiasis and tells us that otoconia is freely floating. Reversing of positional nystagmus has not been reported in patients with ageotropic lateral canal BPPV so far. Second, the side with reversing nystagmus associated with geotropic positional nystagmus clearly indicates the side of pathology. All patients in this series benefit from barbeque maneuver in the opposite direction of the side with reversing nystagmus.

The true incidence of this phenomenon is not known. Longer recording time up to 5 minutes has been recommended in patients with geotropic type lateral canal BPPV to catch more cases [

10]. However, the underlying cause is also not clear. In the presented series and cases in the previous reports, trauma is the leading factor in majority of them. Maybe, the amount and dispersal of otoconial debris is different than regular cases. It is also interesting to note that slow phase velocity of initial nystagmus in these cases is high (between 30-50 deg/sec) indicating a powerful endolymphatic flow [

7]. Reversal of nystagmus in patients with posterior canal BPPV has been reported to be quite rare. The reason is not clear. However, endolymphatic reflux theory would also explain the occurrence of reversal of nystagmus in these cases, if we could assume that the otoconia is located away from the ampulla, close to the common crus [

12,

14].

Patients with unilateral vestibular dysfunction like vestibular migraine, Meniere disease, vestibular neuronitis may present positional nystagmus. This condition can be regarded as intensification of spontaneous nystagmus by positional maneuvers which is sometimes not quite clear during primary gaze position. Acute unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction creates vestibular asymmetry which results from a unilateral change of the resting neural input. In unilateral hypofunction, head movement to each side exposes nonlinearity as specified by Ewald’s second law. This type of nystagmus keeps beating as long as the patient’s head is held in this position. It is associated with prolonged stimulation of normal vestibulo-oculomotor system [

15]. However, peripheral type positional nystagmus in BPPV is confirmed with the presence of latency, short duration, and adaptation of the transient nystagmus.

In conclusion, statements explaining the mechanism of BPPV variants are pretty much theoretical and are based on observational reports. The design of this study is a retrospective review of BPPV variants associated with reversal of positional nystagmus with a presentation of our clinical data. The amount and dispersal of debris or the position of the head and cupula during testing may be related with the occurrence of second-phase nystagmus. Longer recordings of nystagmus in patients with lateral canal involvement is particularly recommended not to miss the cases with direction-changing positional BPPV. From the presented cases and cases in previous reports, we suggest that reversal of positional nystagmus is related with freely floating otoconia in the semicircular canal. Bilateral cases are likely to be simultaneous presentation of co-existence of canalo-and cupulolithiasis in the same ear. This is also important from therapeutical aspects since more maneuvers may be required. Trauma seems to be the main cause. Having a quite intense initial nystagmus in almost all cases, we may consider an excessive amount of otoconial debris entering the canal which create a powerful flow.