This study investigated the brainstem neural encoding using the S-ABR test in CI-recipients, and NH counterparts in the sound-field presentation. The main finding in this study regarding sound-field S-ABR was all wave latency increment in the CI-recipient group, than in the NH group. This finding was consistent with the study conducted by Gabr and Hassaan [

13], demonstrating that all wave latency in children with CI was longer than that of NH children. This outcome was also in agreement with the study of Galbraith, et al. [

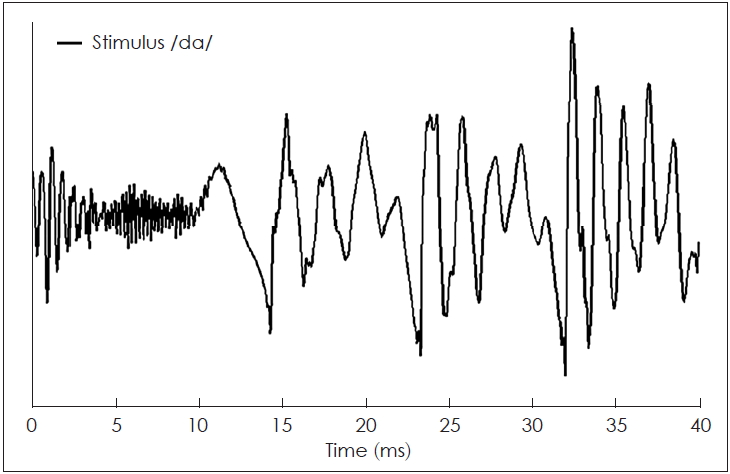

16], where the results suggested that CI users may require a longer time for encoding speech stimuli, than non CI users. Our findings of sound-field S-ABR response demonstrated statistically significant differences between the NH children and CI-recipients. Onset and offset responses in CI-recipients were significantly longer than those of the NH children. The previous studies indicated that a long time is needed for processing the rapid acoustic stimuli, similar to the transient component of /da/ stimuli in the CI-recipient [

11,

17,

18]. This finding is consistent with Nada et al. [

6], who reported a significant delay in the sound-field S-ABR responses initial wave latency in sensory-neural hearing loss. These findings could be defined by several factors, such as the required time for CI-recipients to process acoustical signals, defect in the brainstem response synchrony to the speech stimuli, degraded sound perception, limited language ability, or even a combination of the aforementioned factors [

19].

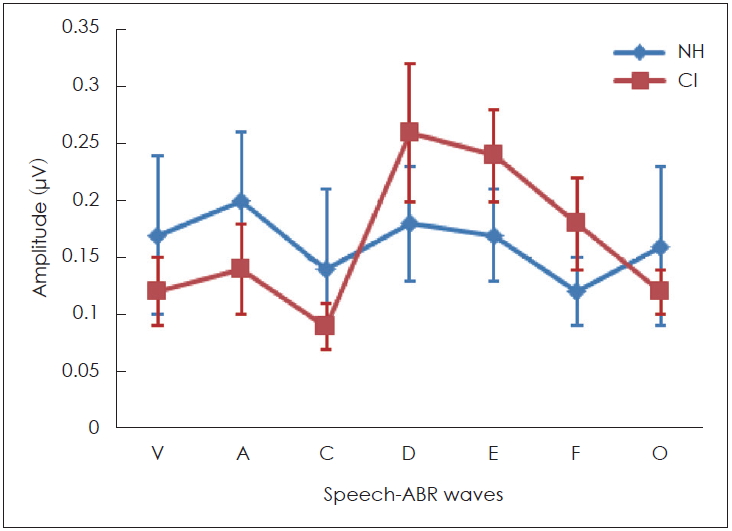

Interestingly, the results of this study demonstrated that some peaks of the sound-field S-ABR amplitude of the CI recipients had higher rate than those of the NH children. As mentioned earlier, the sound-field S-ABR includes two main portions: aperiodic and periodic or FFR waveforms. Results show that the amplitude of the FFR component in the CI-recipient group was higher than that of the NH children group; however, the amplitude of the aperiodic component was lower in the CI-recipient group, than in the NH children group. These results are in agreement with a previous study that reported that the amplitude of sound-field S-ABR aperiodic in CI-recipients group was lower than FFR waveform; however, that study was conducted in two CI-recipients groups, and comparison with normal groups was not performed [

13]. The measure of amplitude in the two studies was not similar. The factors that may account for this discrepancy were the background noise, the participant age, and the different CI prostheses used [

13]. However, the amplitude of sound-field S-ABR responses onset and offset in the NH group was higher, than in the CI-recipient group. These results indicated that the reaction and response to fast and short stimuli, like a transient component of speech stimuli in CI-recipients, were not adequate achieving a reduction in the response amplitude. Generally, many factors may explain the increased FFR response amplitude in CI-recipients, however, the authors considered the electrical current, which directly excites the auditory nerve, whereby the compression role of the basilar membrane is overlooked. Moreover, there was no neurotransmitter release in response to an electrical signal, consequently, the rate of a spike in the first auditory neuron row could be increased, and finally, the maximum rate evoked in electrical stimulation was greater than that in acoustical stimulation [

20,

21]. The most recent important finding was obtained from fast Fourier transform analysis in the spectral domain. This study indicated that the sound-field S-ABR FFR component was not only documented in sound-field presentation, but also as an aperiodic component of speech stimuli. The sound-field S-ABR presence in CI-recipients demonstrated that generally, the speech processing exists at the brainstem level, with respect to the differences seen with normal individuals. Consequently, it was observed that CI devices led to the neural conduction velocity and neural synchrony improvement [

13]. This finding is in agreement with the results of the study conducted by Gama, et al. [

22], which was conducted on 23 participants with NH, for the FFR recording in the sound-field presentation. They demonstrated that FFR waveforms could be reliably elicited in the NH group and CI-recipients group in sound-field, comparable with close-field presentations [

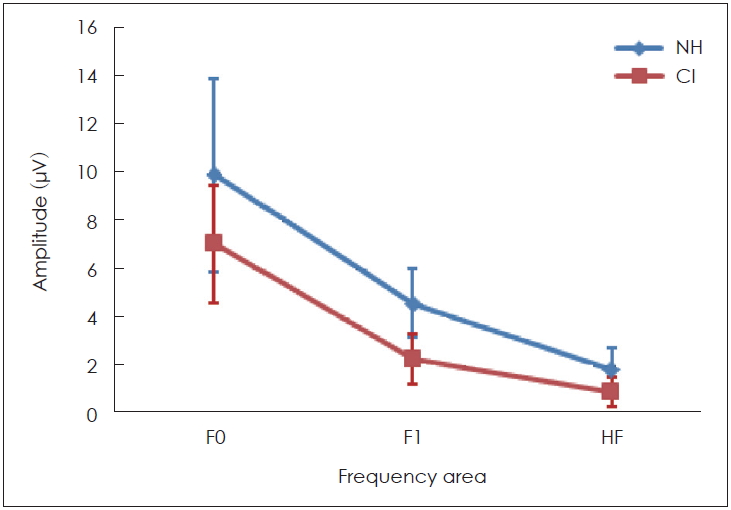

22]. In this analysis, the sin wave magnitude corresponded to the energy level in the complex sound frequency. The spectral analysis was used for phase-locking measurement at F0, F1, and HF. Analysis in the spectral domain of sound-field S-ABR response indicated that the total activity occurring around F0, F1, and HF in NH children were greater, than in CI-recipients. The results indicated that the precision and magnitude of neural phase locking to F0, F1, and HF ranges were lower in CI-recipients. The F0 plays an essential role for perceiving the pitch of a person’s voice, and contains a low-frequency component of speech sound; consequently, recognition of speaker sound, and the voice emotional tone is dependent on the F0 encoding [

23]. Furthermore, F1 and HF are a series of the discrete peak in the formant structure that are responsible for the vowel perception, and provide some information regarding the stimuli phonetics; therefore, it could play a significant role in different capabilities of CI-recipients, and normal individuals in the different spectral processing at the brainstem level to speech signals [

24]. As mentioned earlier, speech perception in CI recipients is weaker than in the NH counterparts; however, in this study, we found that F0, F1, and HF were lower, in the subcortical area in CI-recipients, than in NH children. Consequently, this study indicated physiological evidence for weak speech perception abilities, such as identifying the speaker and emotional voice, and poor performance in perceiving vowel and phonetic information. These results are in agreement with the findings of Rocha-Muniz, et al. [

11], which demonstrated that spectral amplitude of speech sound was decreased in auditory processing disorder, and language impairment.

Therefore, these findings demonstrate that CI-recipients indicated delayed latency for sound-field S-ABR response than the NH children did. The FFR component amplitude in sound-field S-ABR of CI-recipient group was increased, than that of the NH group, while this increased amplitude was not observed in the aperiodic component of sound-field S-ABR. Spectral analysis of sound-field S-ABR responses indicated that CI-recipients have neural encoding deficits for timing features, than NH children do. The decrease in F0, F1, and HF spectral amplitude can result in weak performance of the CI-recipients in speech processing. The findings of this study added valuable information regarding brainstem auditory processing amongst children with CI, and NH counterparts in the sound-field presentation.

In the current study, the findings of sound-field S-ABR demonstrated that CI-recipients had neural encoding deficits in temporal and spectral domains at the brainstem level, than the NH children did. Therefore, the sound-field S-ABR, as an objective, non-invasive, and efficient clinical procedure, is useful for assessing the speech processing at the brainstem level in CI-recipients. Future research is warranted to measure the S-ABR in CI-recipients with different speech recognition abilities.